Software Design is a creative industry without auteurs. We reference, borrow, and build on each other’s ideas without ever actually creating them. Creativity, when put under a microscope, looks more like a step ladder than the geography of Pandora. The ideas of usability, elegance, simplicity, and fun preached by the best designed products don’t actually belong to anyone. They’re a collective unconscious we’ve deemed as good that we try to tap into with our digital selves.

In some ways, whether a design accomplishes its goal or not can feel like a matter of chance. There’s a belief that The Process will lead to the desired outcome by simply abiding to it for enough repetitions. It’s both disempowering and liberating at once: anyone that properly employs The Process for long enough will achieve success. The Designer is simply a replaceable variable responsible for pressing the right button in the right order at the right moment in time.

So we cope and say “I am not my work.” We tell ourselves that work and life are two separate forces that need to be balanced. We divide our waking hours in half, craft a “work me” and a “real me”, and then suppress our inconvenient human urges to achieve post-modern nirvana: collective productivity. Designers, in particular, have learned to disassociate even further. We’ve been asked to inject creativity into The Process and somehow remove our personal selves from it. We all repeat the mantra: I am not my work.

This idea is masterfully explored in Ben Stiller’s Severance, which depicts a world where workers voluntarily opt into a program that surgically removes people’s memories outside of work. The horror of this concept becomes self evident almost immediately and, beyond asking provocative questions like “what makes you you?”, it highlights the utter nonsense and delusion of work/life balance.

You are your work in the same way that you are anything and everything: a paella of experiences.

That’s why looking for a job can be so painful to so many of us. The job-hunting process is self-indulging by nature. With every recruiter call or on-site loop, you’re presenting and selling not just your work but yourself (or rather, the part of yourself you chose to expose to work). You try to convince a stranger that they can trust you with their product, give you a lump of money and, ultimately, convince them (and you) that you’re worth it.

It’s easy to think that our “worth” is in fact described by the lump of money or job title behind an offer letter. After all, how else can we get a clear assessment of our value? We go about our lives improvising an answer to the question “what would a good person do?” with little clue on what good actually means. So we settle for just doing. And we all do. Constantly.

In her book “How To Do Nothing”, Jenny Odell beautifully juxtaposes the urge to do:

To resist in place is to make oneself into a swap that cannot so easily be appropriated by a capitalist value system. To do this means refusing the frame of reference: in this case, frame of reference in which value is deterred by productivity, the strength of one’s career, and individual entrepreneurship. It means embracing and trying to inhabit somewhat fuzzier or blobbier ideas: of maintenance as productivity, of the importance of nonverbal communication , and of the mere experience of life as the highest goals. It means recognizing and celebrating a form of the self that changes over time, exceeds algorithmic description, and whose identity doesn’t always stop at the boundary of the individual.

I love this book because it served as an almost anti-bible for me. Jenny stands like an immovable object in front of the unstoppable force of productivity that reigns over my (and I suspect most people’s) life. It dares to stay still and resist the inertia of creating things, growing, and progress. Instead, it presents a more profound idea: there’s value in simply existing and looking not at what we can do but what we have done. Jenny continues:

But beyond self-care and the ability to (really) listen, the practice of doing nothing has something broader to offer us: an antidote to the rhetoric of growth. In the context of health and ecology, things that grow unchecked are often considered parasitic or cancerous. Yet we inhabit a culture that privileges novelty and growth over the cyclical and the regenerative. Our very idea of productivity is premised on the idea of producing something new, whereas we do not tend to see maintenance and are as productive in the same way.

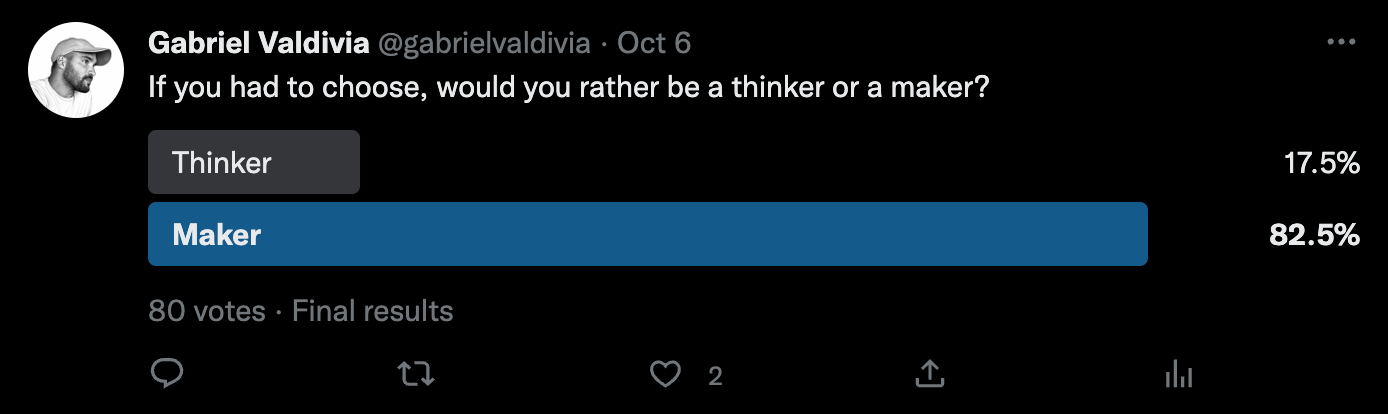

The idea and value of creating things is very much in the zeitgeist as of late. In a totally scientific poll, over 80% of people would describe themselves as “makers.”

Needless to say, AI is rapidly changing our understanding of what making really is. Its proponents defend it as a tool. They argue that makers will always embrace tools to be creative. Another defense I’ve heard is that it isn’t the final output but a “tool” to help makers through generative thinking. They see “making” evolving from whatever it is today to the curation of AI input followed by the refinement of the results by applying your human flair.

People like Ammaar, a tech worker who “made” a children’s book through AI in a weekend, may very well be turning writers and illustrators into the next coal miners. Some would argue he’s a curator, not a creator. When I dug further, people seem to prefer creation over curation.

Is AI a creative tool or an existential threat to creativity? Does it matter?

Yuval Harari predicts that by 2050, AI will advance to the point of taking over most tasks performed by humans. At its best, AI could lead to a world of abundance where most menial tasks are performed by an AI. Resources are mined beyond efficiently and humans are left to rest. Yuval predicts that humanity will lack sufficient education or mental stamina to continue learning new skills and thus will become a “useless class.”

I’d argue that a class without use is not a class without value. That is to say, our value need not derive from our usefulness, what we do, or create. Our value can, in fact, derive from just being. A concept so foreign that it makes my skin crawl. But perhaps, the most human concept.

I ain’t no maker. This ruled, and reminded me of a book on this subject that really influenced my life: Pieper’s “Leisure, the Basis of Culture.” It’s an extremely fun read.

I wrote about it a million years ago here (apologies for the busted formatting; they must have changed how this post type works): https://metaismurder.com/post/14315368974/we-have-forgotten-leisure-as-non-activity-an